Diane promised she would never be like her friend, Sara, who was always yelling (often screaming) at her kids, “Don’t do that! Do this! I’m sick and tired or telling you!” On and on! It was difficult for Diane to be around Sara, and she felt so sorry for the kids.

One day Diane found herself telling three-year-old Seth, “Don’t do that! Come here right now! Pick up your toys! Get dressed!” And on and on! Fortunately she heard herself and said to her husband, “Oh my; I sound like just like Sara. Gently he said, “I didn’t want to say anything, but yes you do.”

Diane remembered what she had read in Positive Discipline Birth to Three about acting without words and decided to try it for one whole day. When Diane wanted Seth to stop doing something, she walked over to him, took him by the hand, and removed him. When she wanted him to come to her, she got off the couch and went to him to show him what needed to be done. When he started hitting his little brother, Diane gently separated them without saying a word.

During a calm time, Diane sat down with Seth and said, “Let’s play a game. When I want you to do something, I’ll keep my lips closed tight and will point to what needs to be done and you can see if you know what I want without me saying a word. Okay?” Seth smiled and agreed.

When it was time to pick up his toys, Diane went to him, grinned and pointed to the toys while making a sign with her hands for him to pick them up—and then helped him, knowing that it is encouraging and effective to help children with tasks until they are at least six-years-old and can “graduate” to doing tasks by themselves. When it was time for him to get dressed, she took him by the hand, made a zipping her lips sign, and pointed to his clothes. Seth grinned and let Diane help him get dressed without a struggle—doing most of it by himself.

Later Diane shared with her husband how much more peaceful her day had been, and how much more she enjoyed her interactions with Seth. Diane added, “I know actions without words won’t work all the time, but this day sure helped me realize how important it is to at least get close enough to see the white in his eyes before I talk—and then to use more action and fewer words.”

Monday, June 30, 2014

Monday, June 23, 2014

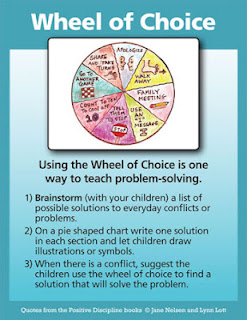

The Wheel of Choice

A primary theme of Positive Discipline is to focus on solutions. The wheel of choice provides an excellent way to focus on solutions, especially when kids are involved in creating the Wheel of Choice. Some parents and teachers have their kids make the wheel of choice from scratch. This Wheel of Choice was created by 3-year-old Jake with the help of his mom, Laura Beth. Jake chose the clip art he wanted to represent some choices. His Mom, shared the following success story.

Jake used his Wheel of Choice today. Jake and his sister (17 months old) were sitting on the sofa sharing a book. His sister, took the book and Jake immediately flipped his lid. He yelled at her, grabbed the book, made her cry. She grabbed it back and I slowly walked in. I asked Jake if he’d like to use his Wheel Of Choice to help—and he actually said YES! He chose to “share his toys.” He got his sister her own book that was more appropriate for her and she gladly gave him his book back. They sat there for a while and then traded!

The Wheel of Choice below is from a program created by Lynn Lott and Jane Nelsen (illustrations by Paula Gray). It includes 14 lessons to teach the skills for using the Wheel of Choice. Click Here to get a more complete description and to order your own Wheel of Choice: A Problem Solving Program.

After teaching all the lessons to her students, and having them color their individual slices of the wheel after each lesson, one teacher asked her students to choose their four favorite solutions from the their wheel of choice. They then cut them out and made mobiles to hang above their desks so they could look up and remember their favorite solutions to conflict. Kids are great at focusing on solutions when we teach them problem-solving skills.

Monday, June 16, 2014

Hugs: A Positive Discipline Tool Card

By Jane Nelsen, author and co-author of the Positive Discipline series

This tool card provides an example of asking for a hug when a child is having a temper tantrum, but that is certainly not the only time a hug can be an appropriate intervention when you understand the principle of hugs. Later, I’ll share where the example on the card came from; but first I want to share another example illustrated in a story shared by Mary Wardlow:

My daughter Madisyn, who is a wonderfully strong-willed six-year-old child, didn't want to get up and get ready for school one morning. Being a strong-willed individual myself, I could sense a battle of wills brewing—though I was determined to avoid it. I repeatedly asked her nicely to get up and get herself ready. I even picked out her clothes so she could move a little faster [a mistake that will be explained later]. Still, she refused to move. I reminded her, still nicely, that the bus would be at our house soon, and if she didn't get dressed she was going to miss it.

She sat up, looked at her clothes, and screamed, "I don't want to wear that!" Her tone was so nasty that I found it hard to keep myself composed, but I went to her room and picked out two other outfits so she could choose which one she wanted to wear. I announced to her, "I laid out three sets of clothes. You need to pick one and get dressed." I had almost made it to the bedroom exit when she fired back "I WANT FOUR!"

I was so angry at that point; and what came next surprised both of us. I walked over to her and said, "Madisyn, I am going to pick you up, hold you, hug you and love you...and when I am done you are going to get up, choose an outfit and get dressed."

When I picked her up and put my arms around her I felt her just melt in my arms. Her attitude softened immediately and so did mine. That moment was amazing to me. A volatile situation turned warm in a few seconds—just because I chose to hug a child who was at that moment so un-huggable.

In your lecture you talked about the power of a hug to calm down an out-of-control child. I've learned first-hand that you were absolutely right. Thank you for teaching others about the power of a hug!

Later Mary learned that the morning hassles could be reduced if her daughter picked out her own clothes the night before as part of her bedtime routine. This would help her feel capable instead of being told what to do, which invited rebellion. This example illustrates that even though hugs work to create a connection and change behavior, some misbehavior can be avoided by getting children involved in ways that helps them use their power in useful ways—for example picking out their own clothes.

Now for the story that led to the example of asking for a hug when a child is having a temper tantrum. I watched a video of Dr. Bob Bradbury, who facilitated the “Sanity Circus” in Seattle, WA for many years. During Sanity Circus, Dr. Bradbury would interview a parent or teacher in front of a large audience. During the interview he would determine the mistaken goal of the child and would then suggest an intervention that might help the discouraged child feel encouraged and empowered. Bob shared the following example (which I am now telling in my words from my memory of what I saw on the video).

A father wondered what to do about his four-year-old, Steven, who often engaged in tempter tantrums. After talking with the father for a while, and determining that the mistaken goal was misguided power, Dr. Bradbury suggested, “Why don’t you ask your son for a hug.”

The father was bewildered by this suggestion. He replied, “Wouldn’t that be reinforcing the misbehavior?”

Dr. Bradbury said, “I don’t think so. Are you willing to try it and next week let us know what happens?”

The father agreed with misgivings. However, the next week he reported that, sure enough, Steven had a temper tantrum. Dad got down to his son’s eye level and said, “I need a hug.”

Between loud sobs, Steven asked, “What?”

Dad repeated, “I need a hug.”

Steven was still sobbing but managed to ask incredulously, “Now????”

Dad said, “Yes, now”

Steven stopped sobbing and said, reluctantly, “Oh all right,” as he stiffly gave his father a hug. In a few seconds he just melted into his fathers arms.

After they hugged for a few more seconds, Dad said, “Thanks. I really needed that.”

Steven sniffled a bit and said, “So did I.”

There are a few points I want to make about this story. You may wonder why the father said, “I need a hug,” instead of, “You need a hug.”

1) Since the mistaken goal in this case was “misguided power.” To suggest that his son needed a hug would like invite him to say, “No I don’t,” and only intensify the power struggle. How could Steven argue with the fact that his father needed a hug?

2) Children have an innate desire to contribute. Contribution provides feelings of belonging, significance, and capability. Steven really wanted to “give” to his father, even though begrudgingly at first.

3) Children do better when they feel better. Once Steven felt better by giving his father a hug, he let go of his tantrum and the power struggle and enjoyed the hug with his father.

4) A misbehaving child is a discouraged child. It can be difficult to remember this when faced with annoying, challenging, or hurtful behavior. For this reason it helps to have a plan for behavior that is a pattern.

5) A primary philosophy of Positive Discipline is Connection before Correction. A hug is a great way to make a connection, but not the only way. I will mention a few more of the many possibilities:

6) Simply validate your child’s feelings. “You are feeling really upset right now.” Then step back and give energetic support while your child works through it.

7) Name what is happening and then offer an alternative. For example:

“It seems to me that we are in a power struggle right now. I love you and know we can work on a win/win solution if we wait until we calm down.” Or,

“I can see you really want my attention right now. I love you and I don’t have time right now but I’m looking forward to our special time at 7:30.” (Of course, this requires advance planning to make sure you have set up scheduled, special time with your children.

8) Do the unexpected. Instead of reacting to the challenging behavior, ask your child. “Do you know I really love you?” This sometimes stops the misbehavior because your child is so surprised by your question/statement, and may feel enough belonging and significance from that simple statement to “feel better and do better.”

There are many other possibilities to make a connection and to help children feel better so they’ll do better. However, the main point is to see all of the Positive Discipline Tool cards NOT as techniques, but as principles. Techniques are very narrow and often don’t work. A principle is wider and deeper—and there are many ways to apply a principle. Go into your heart and your wisdom and you’ll know how to apply the principles of connection before correction, focusing on solutions, empowering children—and hugs—that are even better than the examples.

A Positive Discipline Tool Card (available at www.positivediscipline.com)

This tool card provides an example of asking for a hug when a child is having a temper tantrum, but that is certainly not the only time a hug can be an appropriate intervention when you understand the principle of hugs. Later, I’ll share where the example on the card came from; but first I want to share another example illustrated in a story shared by Mary Wardlow:

The Power of a Hug

My daughter Madisyn, who is a wonderfully strong-willed six-year-old child, didn't want to get up and get ready for school one morning. Being a strong-willed individual myself, I could sense a battle of wills brewing—though I was determined to avoid it. I repeatedly asked her nicely to get up and get herself ready. I even picked out her clothes so she could move a little faster [a mistake that will be explained later]. Still, she refused to move. I reminded her, still nicely, that the bus would be at our house soon, and if she didn't get dressed she was going to miss it.

She sat up, looked at her clothes, and screamed, "I don't want to wear that!" Her tone was so nasty that I found it hard to keep myself composed, but I went to her room and picked out two other outfits so she could choose which one she wanted to wear. I announced to her, "I laid out three sets of clothes. You need to pick one and get dressed." I had almost made it to the bedroom exit when she fired back "I WANT FOUR!"

I was so angry at that point; and what came next surprised both of us. I walked over to her and said, "Madisyn, I am going to pick you up, hold you, hug you and love you...and when I am done you are going to get up, choose an outfit and get dressed."

When I picked her up and put my arms around her I felt her just melt in my arms. Her attitude softened immediately and so did mine. That moment was amazing to me. A volatile situation turned warm in a few seconds—just because I chose to hug a child who was at that moment so un-huggable.

In your lecture you talked about the power of a hug to calm down an out-of-control child. I've learned first-hand that you were absolutely right. Thank you for teaching others about the power of a hug!

Later Mary learned that the morning hassles could be reduced if her daughter picked out her own clothes the night before as part of her bedtime routine. This would help her feel capable instead of being told what to do, which invited rebellion. This example illustrates that even though hugs work to create a connection and change behavior, some misbehavior can be avoided by getting children involved in ways that helps them use their power in useful ways—for example picking out their own clothes.

Tantrums and Hugs

Now for the story that led to the example of asking for a hug when a child is having a temper tantrum. I watched a video of Dr. Bob Bradbury, who facilitated the “Sanity Circus” in Seattle, WA for many years. During Sanity Circus, Dr. Bradbury would interview a parent or teacher in front of a large audience. During the interview he would determine the mistaken goal of the child and would then suggest an intervention that might help the discouraged child feel encouraged and empowered. Bob shared the following example (which I am now telling in my words from my memory of what I saw on the video).

A father wondered what to do about his four-year-old, Steven, who often engaged in tempter tantrums. After talking with the father for a while, and determining that the mistaken goal was misguided power, Dr. Bradbury suggested, “Why don’t you ask your son for a hug.”

The father was bewildered by this suggestion. He replied, “Wouldn’t that be reinforcing the misbehavior?”

Dr. Bradbury said, “I don’t think so. Are you willing to try it and next week let us know what happens?”

The father agreed with misgivings. However, the next week he reported that, sure enough, Steven had a temper tantrum. Dad got down to his son’s eye level and said, “I need a hug.”

Between loud sobs, Steven asked, “What?”

Dad repeated, “I need a hug.”

Steven was still sobbing but managed to ask incredulously, “Now????”

Dad said, “Yes, now”

Steven stopped sobbing and said, reluctantly, “Oh all right,” as he stiffly gave his father a hug. In a few seconds he just melted into his fathers arms.

After they hugged for a few more seconds, Dad said, “Thanks. I really needed that.”

Steven sniffled a bit and said, “So did I.”

There are a few points I want to make about this story. You may wonder why the father said, “I need a hug,” instead of, “You need a hug.”

1) Since the mistaken goal in this case was “misguided power.” To suggest that his son needed a hug would like invite him to say, “No I don’t,” and only intensify the power struggle. How could Steven argue with the fact that his father needed a hug?

2) Children have an innate desire to contribute. Contribution provides feelings of belonging, significance, and capability. Steven really wanted to “give” to his father, even though begrudgingly at first.

3) Children do better when they feel better. Once Steven felt better by giving his father a hug, he let go of his tantrum and the power struggle and enjoyed the hug with his father.

4) A misbehaving child is a discouraged child. It can be difficult to remember this when faced with annoying, challenging, or hurtful behavior. For this reason it helps to have a plan for behavior that is a pattern.

5) A primary philosophy of Positive Discipline is Connection before Correction. A hug is a great way to make a connection, but not the only way. I will mention a few more of the many possibilities:

6) Simply validate your child’s feelings. “You are feeling really upset right now.” Then step back and give energetic support while your child works through it.

7) Name what is happening and then offer an alternative. For example:

“It seems to me that we are in a power struggle right now. I love you and know we can work on a win/win solution if we wait until we calm down.” Or,

“I can see you really want my attention right now. I love you and I don’t have time right now but I’m looking forward to our special time at 7:30.” (Of course, this requires advance planning to make sure you have set up scheduled, special time with your children.

8) Do the unexpected. Instead of reacting to the challenging behavior, ask your child. “Do you know I really love you?” This sometimes stops the misbehavior because your child is so surprised by your question/statement, and may feel enough belonging and significance from that simple statement to “feel better and do better.”

There are many other possibilities to make a connection and to help children feel better so they’ll do better. However, the main point is to see all of the Positive Discipline Tool cards NOT as techniques, but as principles. Techniques are very narrow and often don’t work. A principle is wider and deeper—and there are many ways to apply a principle. Go into your heart and your wisdom and you’ll know how to apply the principles of connection before correction, focusing on solutions, empowering children—and hugs—that are even better than the examples.

Wednesday, June 11, 2014

Positive Discipline in Egypt

Lynn Lott and I have been overwhelmed (in a good way), and excited about the spread of our Teaching Parenting the Positive Discipline Way DVD Training. It has now been purchased in 50 countries.

We were delighted to receive these photos from a group of women in Egypt practicing the experiential activities to receive their certificate as Certified Positive Discipline Parent Educators.

We were delighted to receive these photos from a group of women in Egypt practicing the experiential activities to receive their certificate as Certified Positive Discipline Parent Educators.

Monday, June 9, 2014

Allowances Can Teach the Life Skill of Money Management

The Johnson family was about to complete their weekly grocery shopping when five-year-old Jimmy started coaxing for a toy car.

Mom asked politely, "Have you saved enough money from your allowance to buy it?"

Jimmy looked sad and said, "No."

Mom suggested, "Maybe you would like to save your allowance so you can buy that car when you have enough money."

Of course Jimmy never saved enough money to buy the car. He wanted the car bad enough to spend Mom's money, but not enough to save his own money.

Five-year-old Sally wanted a new bicycle. Dad worked out a plan with Sally that as soon as she could save $5.00 toward a bicycle, he would pay the rest. They got a glass jar, pasted a picture of a bicycle on it, and Sally put her whole allowance (four quarters) in the jar the first week. Since Sally's allowance was only $1.00 a week, and it was difficult for her to resist the ice cream truck, it took her three months to save $5.00. This seemed like an eternity to Sally, but every time she brought up the subject of a new bike, her Dad would ask, "How much have you saved?" They would go to the jar, count the quarters, and figure out how many more quarters she needed to reach her goal of $5.00, and Dad would encourage her that she could do it.

In the sixth grade Amy was given a school clothing allowance. Mom and Amy went through her closet together to figure out what she needed, and then sat down to work on a budget to see how much she could spend for each item she wanted to purchase. Amy had to make decisions such as: would she buy two expensive pairs of jeans or four less expensive jeans. During their shopping expedition, many times Mom heard Amy say, "I like this, a little bit, but I don't like it "a lot". I'm not going to buy anything I don't really like a lot."

In the seventh grade Sam started saving diligently for a car because his parents had taken the time to discuss with him that they would not be willing to buy him car when he was 16 unless he put in as much effort as they did. They agreed to match what he saved by the time he was ready for a car—if he had a job so he could buy the gas and insurance. Together they investigated the cost of insurance, and Sam learned that it was much less expensive if he had a "B" average on his report cards and decided he would work hard to maintain a "B" average.

Jimmy, Sally, Amy, and Sam are all learning the value of money. They are learning delayed gratification, goal setting, and the need to work and plan for what they want. They are also learning many side benefits such as cooperation, responsibility, and appreciating what they get. They all made poor decisions along the way. Amy learned to buy only what she "really liked" after buying some things she didn't like so much and then not having money left for things she really liked. Sally finally learned that she wanted a bicycle more than she wanted ice cream. Sam did not save enough money for the car of his dreams, but learned to fix the clunker he purchased because he was too impatient to wait and save a little longer.

Providing allowances is a tool parents can use to teach children many valuable lessons. Too many parents give "handouts" instead of allowances. Handouts are often based on the whims of parents or the ability of kids to coax, whine, and manipulate. Kids believe that checks and credit cards provide an unlimited supply of money. It is a very disrespectful system that leaves everyone feeling bad—parents who feel manipulated by coaxing, crying, or other forms of demand for money, which is never appreciated by their children; and children who do not learn the confidence and self-respect that comes from dealing with money responsibly.

The allowance system is respectful to all concerned. It is negotiated in advance based on what the family can afford and the needs of the kids. If the children's needs are greater than the family budget, they can be encouraged to supplement their income by babysitting, washing cars, or mowing lawns.

Many problems can be avoided when allowances are not tied to chores. A four-year-old may enthusiastically make her bed for 10 cents, but will ask for 50 cents by the time she is eight. By the time she is 14 she won't want to do it even for a dollar.

Connecting chores to allowances offers too many opportunities for punishment, reward, bribery, and other forms of disrespectful manipulation. Each child gets an allowance just because he or she is a member of the family, and each child does chores just because he or she is a member of the family. It can be helpful to offer special jobs for pay that are beyond regular chore routines, such as weeding or washing outside windows. This offers opportunities for kids who want to earn extra money, but does not cause problems if they choose not to take the opportunity.

Allowances can be started when children first become aware of the need for money—when they start wanting toys at the supermarket or treats from the ice cream truck. Some families start with a quarter, a dime, a nickel, five pennies and a piggy bank. A small child loves the variety and enjoys putting the money in the piggy bank. As they get older, allowances can be based on need. They learn budgeting when parents take time to go over their needs with them and decide accordingly on the amount of their allowance.

If kids run out of money before the end of the week it is important to empathize but not rescue. They need the freedom to spend their allowance as they wish. If they spend it all at once they have the opportunity to learn from that experience—so long as parents don't interfere or make judgments. This does not mean that allowances cannot be renegotiated. Renegotiation is an important part of the learning process as kids get older and their needs change. Birthdays or the start of a new school year is a good time to sit down together and look at needs and go over budget planning.

A clothing allowance is a good addition to a regular allowance as soon as kids are old enough to be aware of fashion and want more clothing than is really necessary. A clothing allowance provides limits and encourages responsible decision-making. When children are younger there may be two shopping trips each year—one in the spring and one in the fall, each with a certain dollar amount allotted. As children get older they may get a certain amount each month for them to budget.

Allowance and clothing budgets help children learn what their values are, to make decisions and live with the results, and to use money responsibly. By the time they leave home, they are ready to manage their finances entirely.

Mom asked politely, "Have you saved enough money from your allowance to buy it?"

Jimmy looked sad and said, "No."

Mom suggested, "Maybe you would like to save your allowance so you can buy that car when you have enough money."

Of course Jimmy never saved enough money to buy the car. He wanted the car bad enough to spend Mom's money, but not enough to save his own money.

Five-year-old Sally wanted a new bicycle. Dad worked out a plan with Sally that as soon as she could save $5.00 toward a bicycle, he would pay the rest. They got a glass jar, pasted a picture of a bicycle on it, and Sally put her whole allowance (four quarters) in the jar the first week. Since Sally's allowance was only $1.00 a week, and it was difficult for her to resist the ice cream truck, it took her three months to save $5.00. This seemed like an eternity to Sally, but every time she brought up the subject of a new bike, her Dad would ask, "How much have you saved?" They would go to the jar, count the quarters, and figure out how many more quarters she needed to reach her goal of $5.00, and Dad would encourage her that she could do it.

In the sixth grade Amy was given a school clothing allowance. Mom and Amy went through her closet together to figure out what she needed, and then sat down to work on a budget to see how much she could spend for each item she wanted to purchase. Amy had to make decisions such as: would she buy two expensive pairs of jeans or four less expensive jeans. During their shopping expedition, many times Mom heard Amy say, "I like this, a little bit, but I don't like it "a lot". I'm not going to buy anything I don't really like a lot."

In the seventh grade Sam started saving diligently for a car because his parents had taken the time to discuss with him that they would not be willing to buy him car when he was 16 unless he put in as much effort as they did. They agreed to match what he saved by the time he was ready for a car—if he had a job so he could buy the gas and insurance. Together they investigated the cost of insurance, and Sam learned that it was much less expensive if he had a "B" average on his report cards and decided he would work hard to maintain a "B" average.

Jimmy, Sally, Amy, and Sam are all learning the value of money. They are learning delayed gratification, goal setting, and the need to work and plan for what they want. They are also learning many side benefits such as cooperation, responsibility, and appreciating what they get. They all made poor decisions along the way. Amy learned to buy only what she "really liked" after buying some things she didn't like so much and then not having money left for things she really liked. Sally finally learned that she wanted a bicycle more than she wanted ice cream. Sam did not save enough money for the car of his dreams, but learned to fix the clunker he purchased because he was too impatient to wait and save a little longer.

Providing allowances is a tool parents can use to teach children many valuable lessons. Too many parents give "handouts" instead of allowances. Handouts are often based on the whims of parents or the ability of kids to coax, whine, and manipulate. Kids believe that checks and credit cards provide an unlimited supply of money. It is a very disrespectful system that leaves everyone feeling bad—parents who feel manipulated by coaxing, crying, or other forms of demand for money, which is never appreciated by their children; and children who do not learn the confidence and self-respect that comes from dealing with money responsibly.

The allowance system is respectful to all concerned. It is negotiated in advance based on what the family can afford and the needs of the kids. If the children's needs are greater than the family budget, they can be encouraged to supplement their income by babysitting, washing cars, or mowing lawns.

Many problems can be avoided when allowances are not tied to chores. A four-year-old may enthusiastically make her bed for 10 cents, but will ask for 50 cents by the time she is eight. By the time she is 14 she won't want to do it even for a dollar.

Connecting chores to allowances offers too many opportunities for punishment, reward, bribery, and other forms of disrespectful manipulation. Each child gets an allowance just because he or she is a member of the family, and each child does chores just because he or she is a member of the family. It can be helpful to offer special jobs for pay that are beyond regular chore routines, such as weeding or washing outside windows. This offers opportunities for kids who want to earn extra money, but does not cause problems if they choose not to take the opportunity.

Allowances can be started when children first become aware of the need for money—when they start wanting toys at the supermarket or treats from the ice cream truck. Some families start with a quarter, a dime, a nickel, five pennies and a piggy bank. A small child loves the variety and enjoys putting the money in the piggy bank. As they get older, allowances can be based on need. They learn budgeting when parents take time to go over their needs with them and decide accordingly on the amount of their allowance.

If kids run out of money before the end of the week it is important to empathize but not rescue. They need the freedom to spend their allowance as they wish. If they spend it all at once they have the opportunity to learn from that experience—so long as parents don't interfere or make judgments. This does not mean that allowances cannot be renegotiated. Renegotiation is an important part of the learning process as kids get older and their needs change. Birthdays or the start of a new school year is a good time to sit down together and look at needs and go over budget planning.

A clothing allowance is a good addition to a regular allowance as soon as kids are old enough to be aware of fashion and want more clothing than is really necessary. A clothing allowance provides limits and encourages responsible decision-making. When children are younger there may be two shopping trips each year—one in the spring and one in the fall, each with a certain dollar amount allotted. As children get older they may get a certain amount each month for them to budget.

Allowance and clothing budgets help children learn what their values are, to make decisions and live with the results, and to use money responsibly. By the time they leave home, they are ready to manage their finances entirely.

Monday, June 2, 2014

Sibling Fights: Putting Kids in the Same Boat

If you can’t stand to stay out of your children’s fights, and decide to become involved, the most effective way is to put your children in the same boat. Do not take sides or try to decide who is at fault. Chances are you wouldn’t be right, because you never see everything that goes on. Right is always a matter of opinion. What seems right to you will surely seem unfair from at least one child’s point of view. If you feel you must get involved to stop fights, don’t become judge, jury, and executioner. Instead, put them in the same boat and treat them the same. Instead of focusing on one child as the instigator, say something like, “Kids, which one of you would like to put this problem on the agenda,” or, “Kids, do you need to go to your feel good places for a while, or can you find a solution now?” or, “Kids, do you want to go to separate rooms until you can find a solution, or to the same room.”

Mrs. Hamilton noticed two year old Marilyn hitting eight month old Sally. Mrs. Hamilton felt that Sally had not done anything to provoke Marilyn, but she still put them both in the same boat. First she picked baby Sally up, put her in her crib, and said, "We’ll come get you when you are ready to stop fighting." Then she took Marilyn to her room and said, "Come let me know when you are ready to stop fighting, and we’ll go get the baby."

At first glance this may look ridiculous. Why put the baby in her crib for fighting when she was just sitting there, innocently, and doesn’t understand Mom’s admonition anyway? Many people guess that the purpose of treating them both the same is for the benefit of the older child to avoid feeling always at fault. Treating them the same benefits both children. When you take the side of the child you think is the victim, you are training that child to adopt a victim mentality. When you always bully the child you think started it, you are training that child to adopt a bully mentality.

We can’t know for sure if Sally provoked Marilyn (innocently or purposefully). If she did, reprimanding Marilyn would not only be unfair, but it would teach Sally a good way to get Mother on her side. This is good victim training. If she did not provoke Marilyn, reprimanding Marilyn (because she is the oldest) would teach Sally the possibility of getting special attention by provoking Marilyn. Marilyn might then adopt the mistaken belief that she is most significant as the bad child.

Still, people object that it doesn’t make sense to put a baby, who did nothing wrong, in her crib. Okay, okay. I’ll give you another alternative, but first I want to explain again. The point is not who did what. The point is that you treat both children the same so one doesn’t learn victim mentality and the other doesn’t learn bully mentality. Surely, the baby won’t be traumatized by being put into her crib for few seconds. Another way to put children in the same boat is to give them both the same choice. "Would you both like to sit on my lap until you are ready to stop fighting?" Do or say whatever is comfortable for you—so long as they are treated the same.

I can still hear objections. But, what if the older child really did hit the younger child for no reason? Shouldn’t the older child be punished? Shouldn’t the younger child be comforted?

Since you have read this far, you know that punishment is not an alternative. It is such a ridiculous example to give to children: "I’ll hurt you to teach you not to hurt others."

I suggest you comfort the oldest child first, and then invite her to help you comfort the youngest. Again this is not rewarding the oldest child for starting it. It is recognizing that, for some reason, the oldest child is feeling discouraged. Maybe she is feeling dethroned by the youngest. Maybe she believes you love the youngest more. The reason isn’t important right now. (Dealing with the belief behind the behavior is.) It is important to know that she feels discouraged and needs encouragement.

Encouragement might look like this: "Honey, I can see that you are upset." (Validating feelings is very encouraging.) "Would a hug help?" (Hugs.) Can you imagine her surprise to receive love and understanding instead of punishment and distain? After she feels better you might say, "Would you be willing to help your little sister feel better? Do you want to give her a hug first, or do you want me to?" Can you see that these gestures encourage loving, peaceful actions?

Suppose the older child is too upset to give you a hug, or to want to hug the baby. Still, make the gesture. Then say, "I can see you aren’t ready yet. I’m going to comfort your sister. When you are ready, you can come help me." The baby is not going to suffer that much more while you take a few minutes to comfort the oldest—and you will avoid victim training that could invite the baby to decide, "The way to be special around here is to provoke my older sister."

If you are hearing these methods with you heart, you will get the idea. Put yourself in the shoes of your children. What would help you the most and teach you the most? And, don’t forget to use your sense of humor.

One father would stick his thumb in front of his fighting children and say, "I’m a reporter for CBC. Who would like to be the first to speak into my microphone and give me your version of what is happening here?" Sometimes his children would just laugh, and sometimes they would each take a turn telling their version. When they told their versions of the fight, the father would turn to an imaginary audience and say, "Well folks. You heard it here first. Tune in tomorrow to see how these brilliant children solve this problem." If the problem wasn’t diffused by then, the father would say, "Are you going to put the problem on the family meeting agenda so the whole family can help with suggestions, or can I meet you here tomorrow—same time, same station—for a report to our audience."

When adults refuse to get involved in children’s fights or put the children in the same boat by treating them the same for fighting, the biggest motive for fighting is eliminated.